Introduction

Canton Tower, Guangzhou, China © Zhou Ruogu Architecture Photography

One of my favourite things when I was a child back in the 1970s was an owl made of string. In some regards it was quite simple: two pieces of interlocking hard plastic with notched edges and a ball of golden thread that you had to wrap around. The clever part was that if you started at the top notch on one side, go to the bottom notch on the next, then to the next top free slot, and so on, eventually you had a pattern that, magically, looked a bit like an owl.

Ok, an owl in itself was not that impressive, but what was intriguing to my younger self was that this owl had a double curved surface with curved edges made of nothing but straight lines! As far as I was concerned straight lines were straight and curves curved: that straight lines could produce curves was quite mind blowing. Yes, while others in the 70’s may have taken recreational pharmaceuticals or immersed themselves in the psychedelic art scene, I had a string-art owl.

What I didn’t realise at the time was that I had been introduced to hyperbolic surfaces and their relative: hyperboloid structures.

Why use hyperboloid structures?

So why are hyperboloid structures of interest today? The two main reasons, apart from aesthetic considerations, are strength and efficiency.

Shabolovka Radio Tower ©Richard Pare

As hyperboloid structures are double curved, that is simultaneously curved in opposite directions, they are very resistant to buckling. This means that you can get away with far less material than you would otherwise need, making them very economical.

Single curved surfaces, for example cylinders, have strengths but also weaknesses. Take a drinks can for example: these are made extremely thin, with sides only a fraction of a millimetre thick, yet contain the pressurised beverage and if stood on end can support the weight of a grown adult even when empty. But, once you have enjoyed the contents, you can push in the side with just a slight pressure from your finger. Alternately, if you were to push with your finger from the inside of the can (being careful to avoid any sharp edges of course) then you will find that you have to apply considerable effort to make any impression.

Double curved surfaces, like the hyperboloids in question, are curved in two directions and thus avoid these weak directions. This means that you can get away with far less material to carry a load, which makes them very economical.

The second reason, and this is the magical part, is that despite the surface being curved in two directions, it is made entirely of straight lines. Apart from the cost savings of avoiding curved beams or shuttering, they are far more resistant to buckling because the individual elements are straight.

This is an interesting paradox: you get the best local buckling resistance because the beams are straight and the best overall buckling resistance because the surface is double curved. Hyperboloid structures cunningly combine the contradictory requirements into one form.

History of Hyperboloid structures

Shukhov Tower Nizhny Novgorod 1896

The first designer to make use of hyperboloid structures was the Russian engineer Vladimir Shukhov. Born in 1853, Shukov built his first hyperboloid lattice tower in Polibino, Lipetsk Oblast in the 1890s, and came to international fame with his tower at the All Russia Exposition in 1896.

Over his career, Shukov built over 200 different hyperboloid towers, with typical heights ranging from 12 to 70m. His crowning glory was the Shokov Tower, also known as the Shabolovka Radio Tower, in Moscow. This reached the dizzying heights of 350m, which was 50m taller than the Eiffel Tower yet, at 2,200 tonnes, used only a quarter of the steel.

If you want to know more about Shukov and his place in Soviet engineering, check out the current Royal Academy of Arts exhibition: Building the Revolution (Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935), which also features Richard Pare’s magnificent photo of the Shokov Tower as its main image.

Hyperboloid applications

Today the most common application of hyperboloid structures is for power station cooling towers, where the shape enables a minimum thickness of the concrete shell and a boost to the cooling airflow due to the Venturi effect of the cross-section. Hyperboloids have also been used to great effect, both structural and architectural, on a number of recent airport towers (Barcelona) and skyscrapers (Port Tower, Kobe, Japan; Aspire Tower, Dubai; Canton Tower, Guangzhou, China). You can find quite a list on Wikipedia.

Canton Tower, Guangzhou, China © Kenny Ip

Apart from hyperboloid towers (mathematically speaking: a hyperboloid of one sheet), the most common form is that of the hyperbolic paraboloid, or hypar for short, used for roofs.

The hypar is one of the three standard shapes for fabric roofs, the other two being the saddle and the conic. While there was a certain fashion for concrete hypar roofs in the third quarter of the 20th century, hypar roofs are normally constructed in fabric or cable net. A notable recent example is the London 2012 Olympic Velodrome. The London 2012 Olympic swimming pool and Beijing 2008 main stadium are also hypar in shape but constructed from steel trusses.

London 2012 Olympic Velodrome © ODA

Modelling Hyperboloids

So how do you create a hyperboloid structure in GSA? There are a number of techniques but they generally involve a twist.

Let’s look at hyperbolic paraboloids first.

- Draw a square or rectangular array of crossed beams, but make sure that all the elements or members are full length: do not split them at the intersection points at this time.

- To make the twist select all the nodes on two adjacent sides, then right click on the middle corner and invoke the Flex command.

- Use a linear flex to move that node up by the appropriate amount and note that all the other nodes, and hence beams, have followed.

- Repeat for the other two sides and you have created your hyperbolic paraboloid.

- To finish simple select all the elements and connect them using the sculpt menu.

Rectangular hypar shells are even easier:

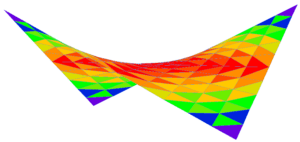

- Take a Quad4 element to cover the whole roof, adjust the corners to the appropriate elevation, then split the warped quad into suitably sized pieces.

- Finish by splitting the Quads into Triangle elements as the Quads will likely be too warped to analyse.

GSA Hypar

The key to hyperboloid towers is the use of cylindrical axes. If you set the current grid (Ctrl+Alt+w) to the Global Cylindrical Axis (or your own as appropriate) you will note that the nodal coordinates are now given not as X, Y, & Z but Radius, Theta (angle) & Z (height).

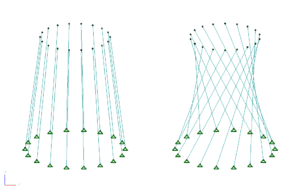

Hyperboloid Twist

- Define a node on the top and bottom rings and join with a beam.

- Copy this round to form a circular array (note that the copy command defaults to the current axis set).

- Mirror all the resulting beams through the radius/theta plane (you will see why in a moment).

- Select all the nodes in the top ring and move them through a suitable theta angle (hint: make it a multiple of the beam spacing).

- Do the same for the twin ring at the bottom but make the angle the negative of that you used at the top.

- Select all the lower beams and Move them (not copy this time) back through the radius/theta plane to make them overlap with the original set.

- Select all the beams and Connect them to form the surface.

- To complete the surface, select all the nodes and extrude them by the angle you used to create the beams, including beam elements along the extrusion to create hoops.

- Alternately, trace Quads onto the beam grillage, split them into triangles, and copy them around. Finish by deleting the beam formwork.

Another way to form a hyperboloid shell tower is to create two nodes, one on the top ring and one on the bottom, with one set at an angle. Join the nodes up with a beam, split the beam into sufficient pieces, delete the beams and extrude the resulting nodes around, creating Quads in the process. Finish by splitting the Quads into Triangles. Note that while the surface will be the same as the previous method, the mesh will be in a different pattern.

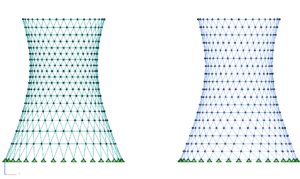

Beam vs Shell meshing

Hyperboloid performance

For the purposes of this article I modelled a cooling tower type shell structure, with a 50m radius base, 35m radius top, a height of 120m and a constant 100mm thickness. Real cooling towers have beams at the base, a varying shell thickness and stiffening rings; mine is a simplification purely for illustrative purposes.

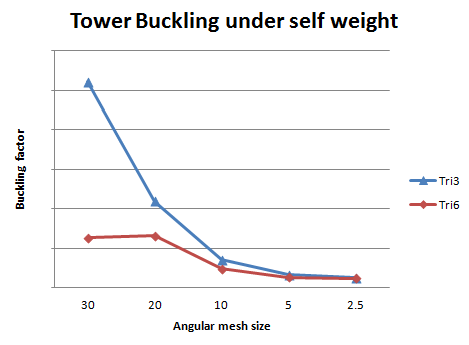

When analysing 2D elements it is vital to ensure that you have a sufficient mesh density. To examine the effect I took a hyperboloid geometry with a 90 deg twist (the top ring is twisted 90 deg in relation to the bottom), then modelled the mesh in sizes ranging from 30 deg down to 2.5 deg, and in both Tri3 and Tri6 elements.

It is a good idea to halve the mesh and re-analyse to see if it makes any difference to the results. In the case of analysing these structures for self weight buckling the results were quite revealing:

Effects of element and size on results

The results showed a convergence (in this case) at the 5 deg mesh size. As you would expect the parabolic Tri6 elements performed better than the Tri3, with the crudest Tri3 giving a buckling factor of 20 times that of the finest mesh. It goes to show that you cannot trust your results if your mesh is too coarse.

There was a clue in the course mesh buckling results though: the modes were directly related to the mesh shapes suggesting that the arbitrary mesh was having too much influence. At other times it may not be so obvious.

Having established a sensible mesh size I then looked at the effect of the twist of the hyperboloid on the self weight buckling. Note that I didn’t analyse for wind, which is likely to be a dominant load case, just the simpler dead load buckling to examine the effect of the geometry on the stiffness.

Increasing the twist from a tapering cylinder (zero deg twist) did give some reduction in weight and surface area.

The twist gave an initial improvement to the tower’s stiffness, but twisting too much reduces the mid height radius, leading to eventual instability.

What was clear was that making the tower a hyperboloid significantly added stiffness, meaning that there are efficiencies to be found and exploited in your designs.

Conclusion

While string-art pictures generally vanished after having a brief craze in the ’70s, hyperboloid structures are useful forms to keep in our engineering toolkit: aesthetic, efficient and easy to model in GSA. I know this thanks to my Aunt who bought a Christmas present for her nephew all those years ago.

Authored by Peter Debney.